Sex Work as Intimacy Work

Too often, “sex work” is reduced to one narrow definition — penetration. But that’s a patriarchal oversimplification. Sex work has always been about more than a single act. It is better understood as intimacy labor: the selling of connection, attention, or presence in a world where those things are scarce.

Consider the spectrum:

Stripping, burlesque, or erotic dance.

Erotic massage without genital contact.

Fetish work, camming, sexting, phone sex.

The “girlfriend experience” dinner date.

Even the companionship of a bartender or hairdresser who remembers your story.

All of these provide intimacy. All of them keep people tethered to something human. And in many cases, people willingly pay for it because they are not finding it elsewhere.

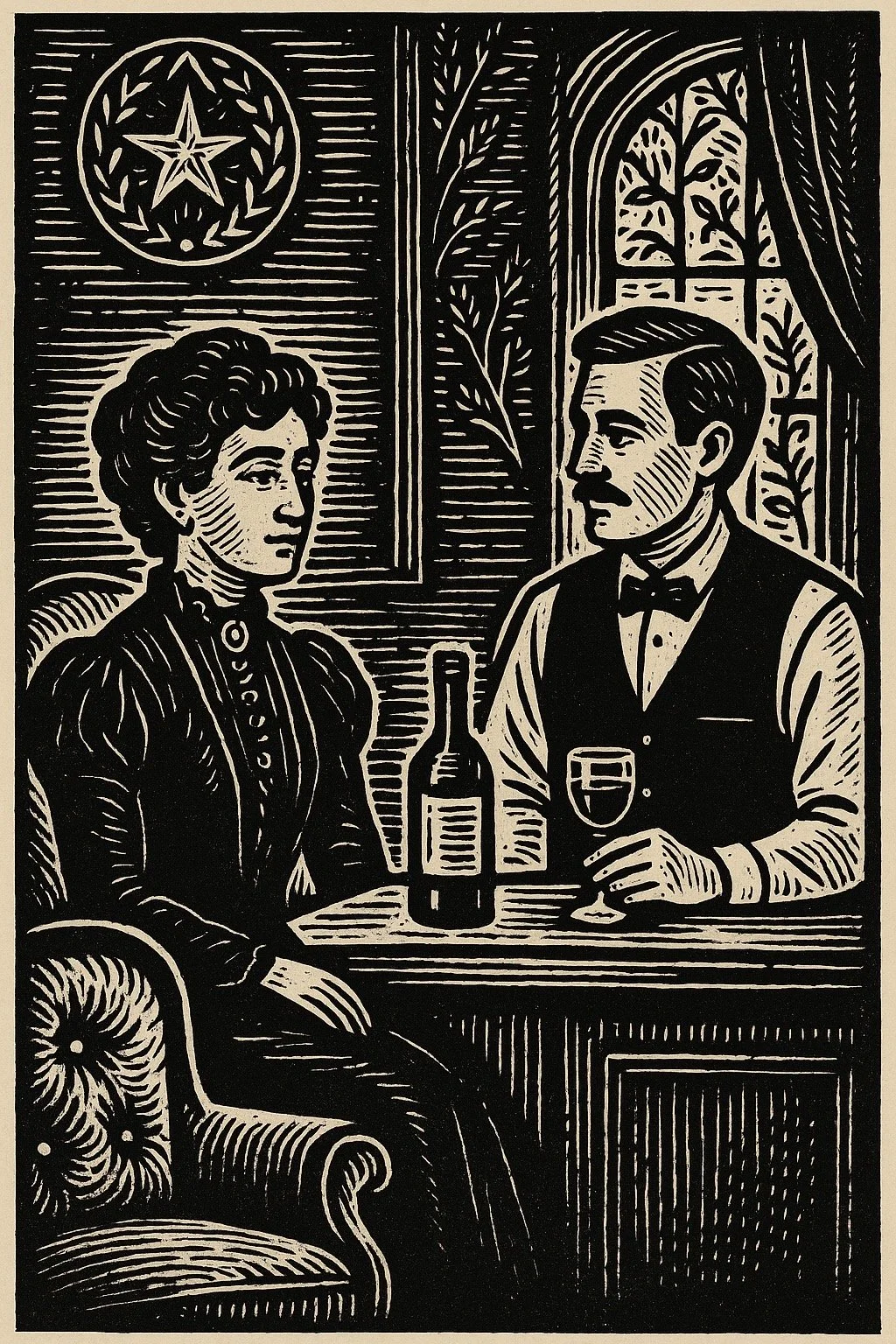

Block print style artwork reimagining Anna Wilson, Omaha’s ‘Queen of the Underworld,’ alongside a bartender — two eras of intimacy work in one room.

Intimacy as a Human Need

Science backs what history and lived experience already know: humans do not survive without intimacy. Studies show that touch lowers stress hormones, reduces pain, and even lengthens lifespan. Emotional intimacy — being heard, being seen, being recognized — plays the same role for the mind. Without these connections, loneliness corrodes health as surely as hunger or thirst.

That need for intimacy explains why sex work has existed in every society across history. It is not a fringe activity; it is the predictable response to a universal human hunger.

Anna Wilson as an Intimacy Entrepreneur

Anna Wilson recognized that hunger before Omaha even had the language for it. In a city that was little more than a railroad town, she created a third space: not home, not work, but a living room for the city.

Her brothel offered sex upstairs, yes — but it also offered shelter, glamour, conversation, and connection. Patrons could drink, socialize, and feel wanted in ways the rest of polite society denied them. Her business lasted for forty years because it delivered something Omaha needed but refused to acknowledge.

Anna was not corrupt. She survived in a system that criminalized her work while quietly relying on it. The “corruption” lay not in her choices but in the city’s willingness to condemn her publicly while benefitting privately.

Hospitality as Intimacy Labor

The connection between sex work and hospitality is closer than most admit. At their core, both professions exist to create a space where people feel seen and cared for. A bartender listens, comforts, and validates. A therapist does the same. A hairdresser or tattoo artist offers touch, conversation, and presence.

Anna’s Place exists in that lineage. It was never meant to be “just a bar.” It was conceived as a modern living room, where intimacy is built through ritual, conversation, and care. That is not a gimmick — it is the very heart of hospitality.

Projects like the Confession Line echo this truth. Guests can call anonymously, leave their stories, and know that someone will hear them. The purpose is not entertainment but recognition: proof that voices matter, even when they are not attached to names. That is intimacy work in its purest form.

Why This Still Matters

COVID-19 stripped entire generations of their formative years of intimacy. High school and college students missed the ordinary social lessons of gathering, flirting, belonging. Many adults learned to live on couches and phones, avoiding face-to-face encounters. Even now, years later, the effects linger. Loneliness is epidemic, and younger generations especially struggle to reestablish what was lost.

This makes intimacy labor more important than ever. People still pay for it — through therapy, bartenders, hair salons, content creators, and sex workers — because the need remains. But as a culture, we continue to shame some forms of this labor while glorifying others.

That is the contradiction Anna Wilson’s story exposes. She gave Omaha its first hospital, cared for her community, and created a space for intimacy long before the city had any infrastructure to provide it. Yet she was vilified, erased, and buried outside respectability.

The same stigma lingers today. Intimacy work is essential, but those who provide it are still marginalized. Hospitality workers are praised as “essential,” but rarely treated with dignity. Sex workers are consumed in secret and shamed in public. Therapists, bartenders, hairdressers, dancers, creators — all of them carry the burden of holding people together, often without recognition.

Anna Wilson’s story matters because it proves the point: intimacy is survival. The people who provide it — whether through sex work, bartending, or any other form — are not corrupt, immoral, or disposable. They are the ones holding the fragile fabric of human connection in place.

And the real question isn’t why Anna Wilson was shamed then. The real question is: why are we still doing it now?